In January of 2018, I attended a panel aimed at millennials to better understand Utah’s Legislative Session. It had been nearly a year since I had graduated from law school, and I was still struggling to find work and searching for purpose. I felt too shy to show up to an event where I didn’t know anyone, so I dragged my husband along and we sat in a crowd of our peers in folded chairs in the rotunda of the Capitol.

The moderator introduced a bipartisan panel of four lawmakers. To kick things off, each was asked to share what their priority was for the Session that would start the following week. Rep. Angela Romero spoke about the bills she was running to address domestic violence and support survivors of sexual abuse. She gave a short but passionate speech about how critical those reforms are in Utah, what she hoped to achieve, and her longstanding commitment to fight for survivors.

Next up was a Republican representative who was, at the time, the youngest legislator in Utah. He paused, and then stated his top priority was raw milk. He was running a bill that would allow people with cows to sell raw milk to their neighbors and friends.

The contrast between those two responses could not have been more apparent. One lawmaker presented herself as deeply connected to her community, leveraging her platform to advance critical issues and advocating for justice for those being failed by the current system. The other, in that moment, did not. I remember feeling embarrassed for him. This young representative had a tremendous opportunity to make a difference, and the most important problem he chose to tackle was raw milk.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent protests against racism and police brutality, a lot of white people–myself included–are waking up to a more complete vision of what racial justice looks like in this country, and the ways in which our current systems are failing Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color. Encouragingly, many are eager to see this energy quickly converted into law. After years and years of watching popular support for systemic reform result in no substantive policy changes (like what’s happened with the movement for gun reform), people are understandably anxious to make sure this momentum counts.

People across the nation are contacting the elected officials with the power to bring justice to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many others whose deaths have not been prosecuted. In Utah, there are also many people contacting their local elected officials to ask what they are doing to ensure justice in our own communities. This is important. We need people making repeated outreach in order to ensure justice in our own communities– for the death of Bernardo Palacios-Carbajal, and for a proactive peace in the future.

At the same time, it’s important to recognize that some lawmakers are way ahead of you. They’ve been doing the work. This is their work. The gift of allyship is that it does not require us to reinvent the wheel. Instead, we can help bring about change by throwing our weight behind the people already rolling the movement forward.

As Rep. Sandra Hollins–Utah’s first and only female Black lawmaker–said in a press conference after Salt Lake City’s first weekend of protests, “I need people at the Capitol pushing with me. I’ve always said I’m willing to push but I need people behind me pushing also. We need the public out there pushing with us, making those phone calls and calling their elected officials and educating them on why certain policies are more important or how certain policies may have an impact on communities of color.”

Rep. Angela Romero remarked on Twitter that she and other elected officials of color had been getting an influx of calls from white constituents anxious for racial justice.

Every member of Utah’s House of Representatives, as well as half of the Senate, is up for reelection this year. The lawmakers you should support in November are the ones who have already been doing the work of peace and justice. If they aren’t committed to that work, don’t wait for them to read books and educate themselves. They can do that on their own time at home; they don’t need to do that on your time at the Capitol.

Over the past several years, Utah has passed several bills that address racial justice directly. They have not passed unanimously. As a minimum, if my elected representative had voted against any of these bills, they would forfeit my vote for reelection. If you want to know how your lawmakers feel about racial justice now, take a look at how they’ve been voting on it. It is literally their job to think about this sort of thing, how public policy affects all of Utah, and all the intersections it contains. The receipts are already out there.

Here are a few examples:

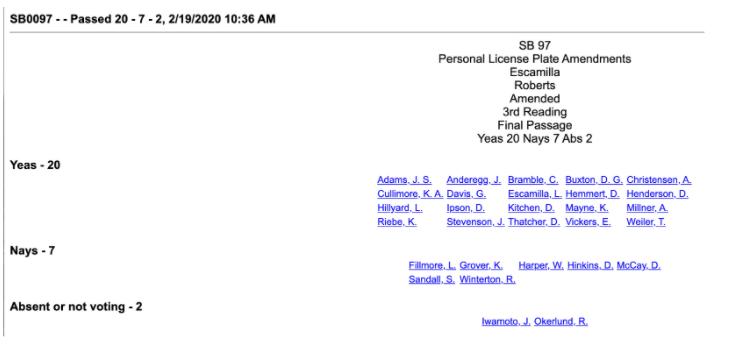

S.B. 97, Personal License Plates Amendments (2020)

Sponsor: Sen. Luz Escamilla

Status: Passed

This bill prevents people from creating racist (or otherwise discriminatory) custom license plates. It passed the House unanimously, but several Senators voted against it.

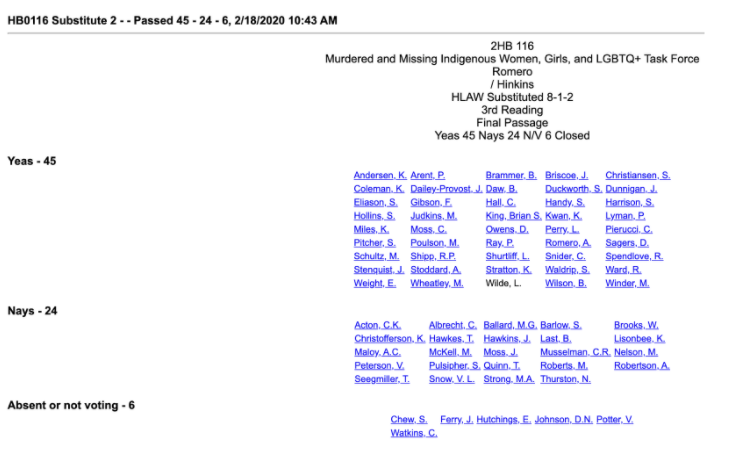

H.B. 116, Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls Task Force (2020)

Sponsor: Rep. Angela Romero

Status: Passed

This bill creates a task force to identify systemic causes behind violence indigenous women and girls experience and recommend improvements in the criminal justice and social service systems. At the time it passed the House, it also included violence against Indigenous LGBT+ individuals. That language was omitted before it went on to the full Senate, where it passed unanimously.

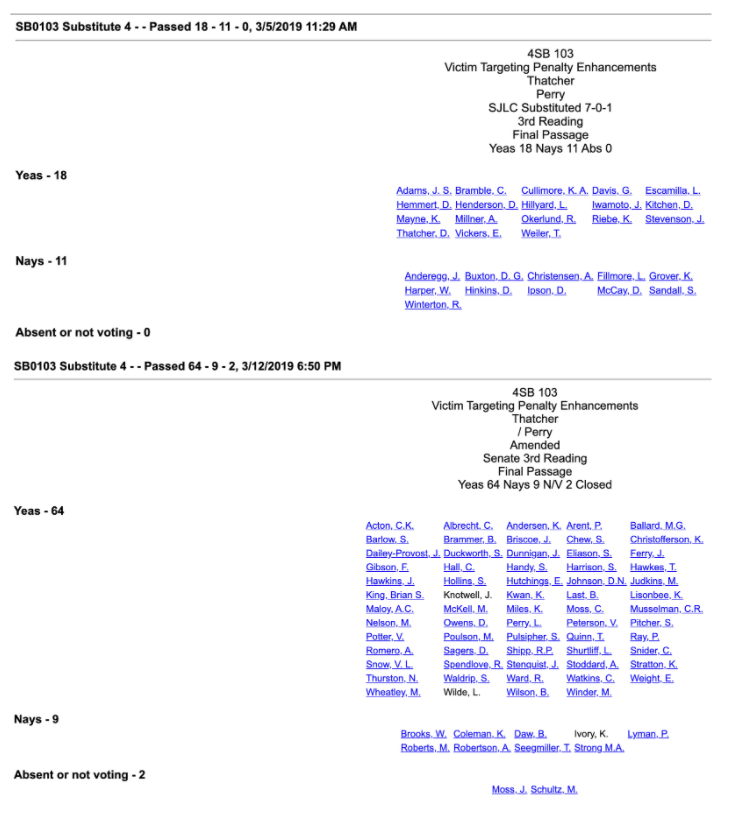

S.B. 103, Victim Targeting Penalty Enhancements (2019)

Sponsor: Rep. Daniel Thatcher

Status: Passed

This bill creates the option of an increased penalty for a “hate crime”– a crime motivated by a person’s race, sex, religion, or some other protected category. It passed, although some Representatives and some Senators voted against it.

This one is complicated, as I have written before. The bill that was passed ended up as a smorgasbord because conservatives could not wrap their heads around the idea that a hate crimes law is designed to protect marginalized communities. Essentially, the conservative pushback to the bill was that “all crimes matter!” A white, conservative lawmaker cried on the House floor that she had been victimized because of the vitriol she received after torpedoing a bill to ban conversion therapy, and got “political expression” added as a protected category. And yet– for all its flaws, this bill still matters. At a time when hate crimes are on the rise, a hate crimes law gives Utah prosecutors the tools to treat crimes motivated by racism or other powerful prejudices appropriately.

Of course, racial justice does not end at stopping overt displays of racism. The presence or absence of racial justice is part of every public policy or system we operate within. As many have noted before, it is not enough to discuss race only terms of police or criminal justice reform.

If we truly aspire to racial justice, we are going to have to do the hard work of applying that lens to all the other policies we care about. Education funding is a racial justice issue. As is access to healthcare, as is air quality, as is affordable housing, as is public transit, as is affordable housing, as is reproductive rights, as is gun violence prevention. The list goes on and on.

Our commitment to racial justice has to deepen, and it also has to broaden. We need to widen our gaze and look at the ways that public policy impacts communities of color. For every public policy, there is probably a racial justice angle. We just have to be looking for it. Utah’s leaders who have already been doing the work can help show us where to look.

Lauren is the policy director for Alliance for a Better Utah.