I have driven down through the state of Alabama approximately 34 times in my life. Every summer and nearly every Christmas, my family would pile into our Chevy Venture and head deep south to visit my grandparents in Vancleave, Mississippi. That trip was the most consistent part of my childhood.

Last week, I returned to Alabama for the ProgressNow All-Staff conference. (When I texted my grandma that I was in Montgomery, she noted I was only four hours away, and why didn’t I just come by with my co-workers after it finished?) Until then, the most I had ever seen of Montgomery was the Wendy’s off of I-65. It felt like such a gift to be able to return there and spend time taking in all the history I hadn’t made time for previously.

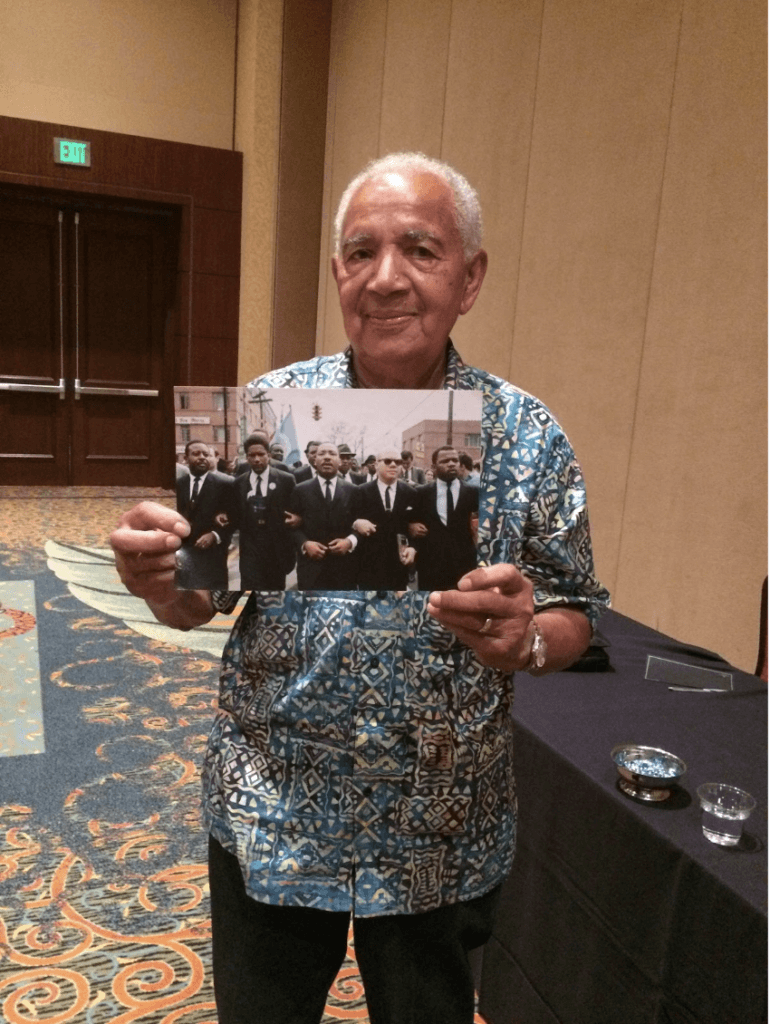

While we were there, we heard from incredible speakers: Lecia Brooks, outreach director at the Southern Poverty Law Center, Justin Hampton, executive director of Common Ground Montgomery, and Nelson Malden, lifelong Montgomery resident and former barber to Martin Luther King, Jr. Nelson was also an usher for the Baptist church where Dr. King preached, and heard many of his sermons over the pulpit. He told us that his grandfather had been a slave, owned by a white man in North Carolina. It was jarring to realize that dark piece history I had grown up reading about in textbooks was not that long ago.

Lecia Brooks described Montgomery as the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement and the cradle of the Confederacy. Seeing those two ideologically opposite movements juxtaposed around the city was surreal: The Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King preached, sits directly across the street from the large, white, plantation-style Alabama State Capitol and the Alabama Supreme Court.

A five-minute walk from the church, the first White House of the Confederacy sits pristine, across from east side of the Capitol lawn.

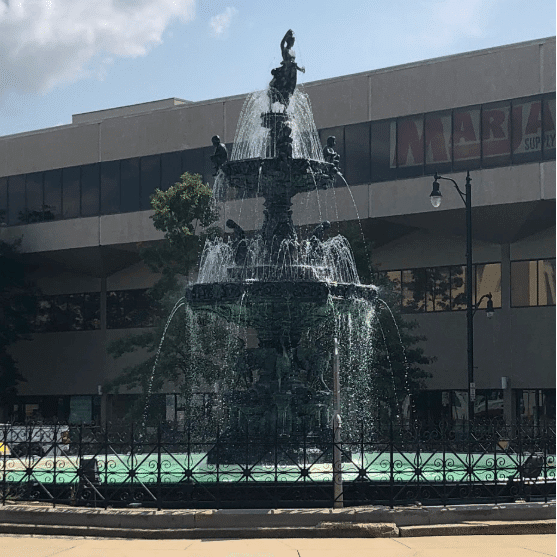

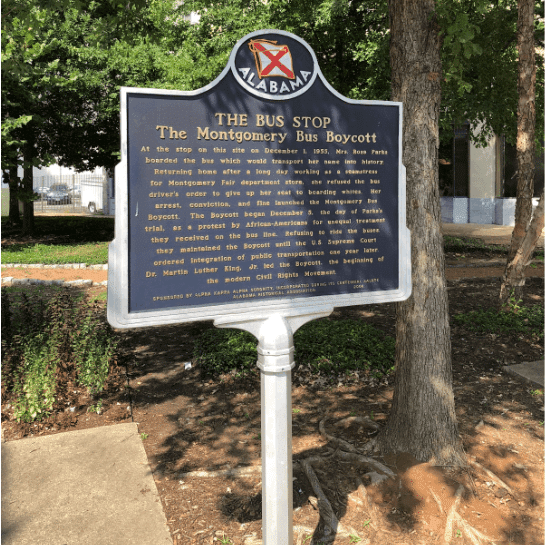

Downtown, the bus stop where Rosa Parks was arrested, ground zero of the Montgomery bus boycott, is located in the same historic square where African-American people were sold as slaves over 150 years ago. The same fountain in the center that looked down upon the marches from Selma also saw families ripped apart and sold like chattel.

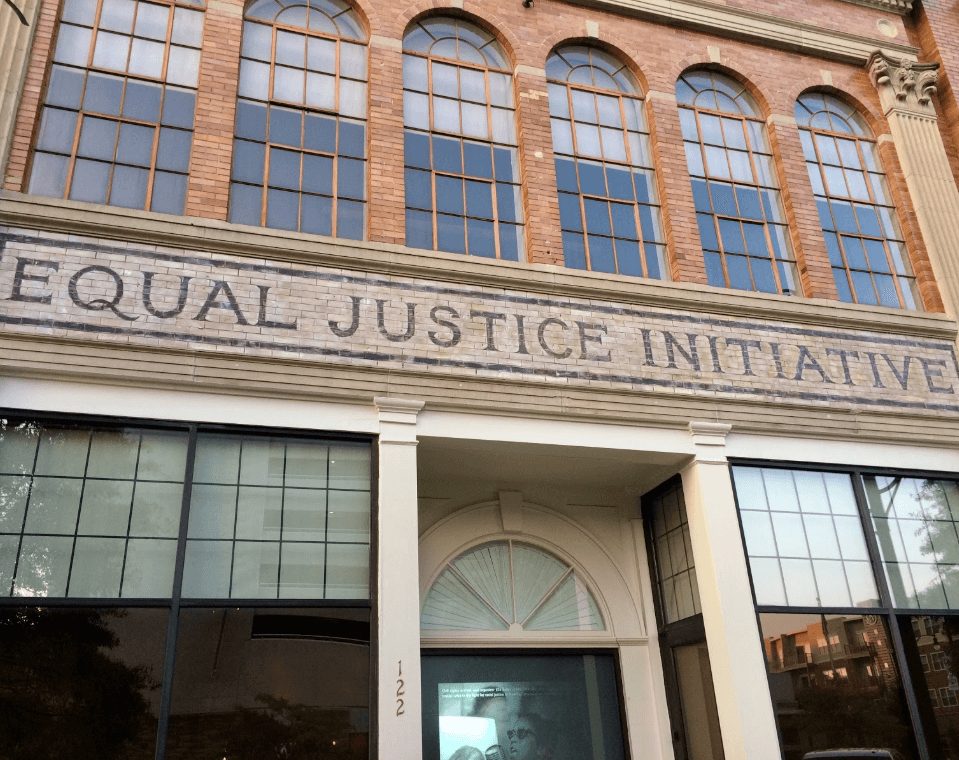

On our last day in Montgomery, we were able to attend the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, honoring the victims of lynchings in the United States. Both the museum and the memorial are run by the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal non-profit that advocates for criminal justice reform.

Built on the foundation of a former holding cell for slaves, the Legacy Museum was substantial and honest and exquisitely human. Like a Holocaust Museum, it is an experience that can only be fully captured in person. It walks visitors through the domestic slave trade in the U.S. to emancipation and the racial violence and Jim Crow laws that followed; through the Civil Rights Movement and the subsequent tough-on-crime administrations that targeted communities of color through the “war on drugs.” It concludes with our status quo of mass incarceration and an overly punitive justice system biased against brown and black bodies.

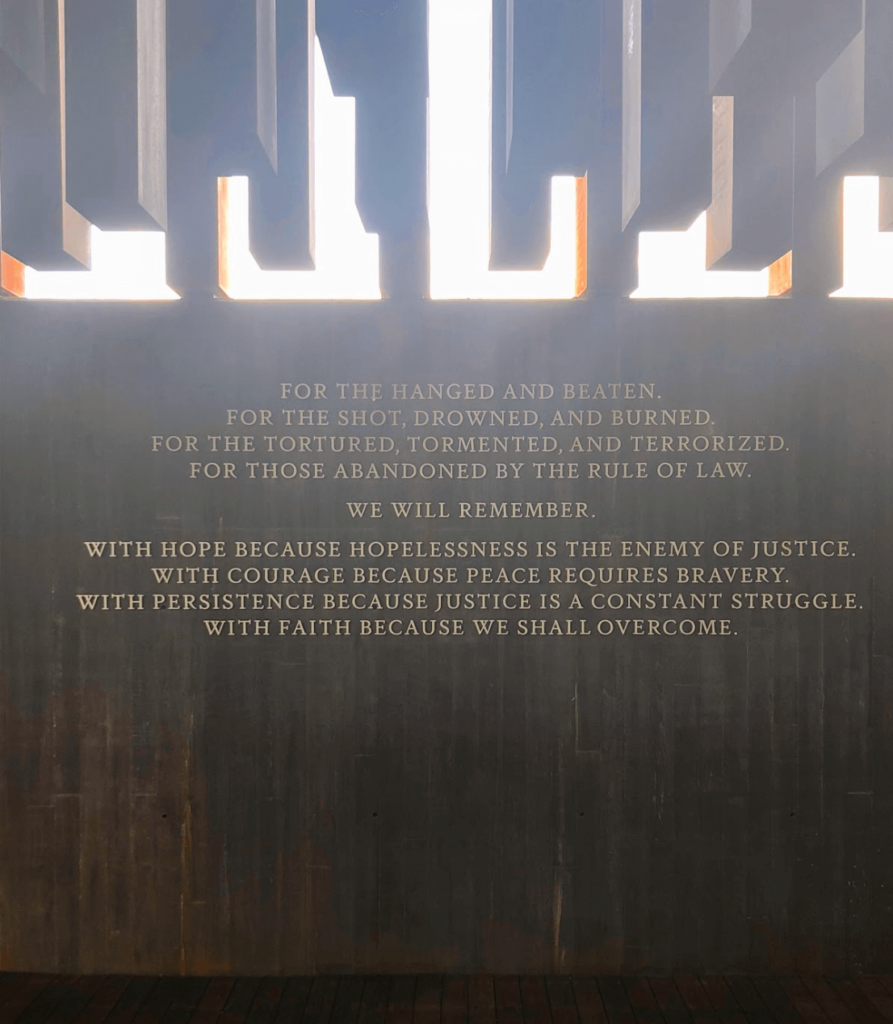

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice specifically focuses on those persons who were killed in lynchings in the United States.

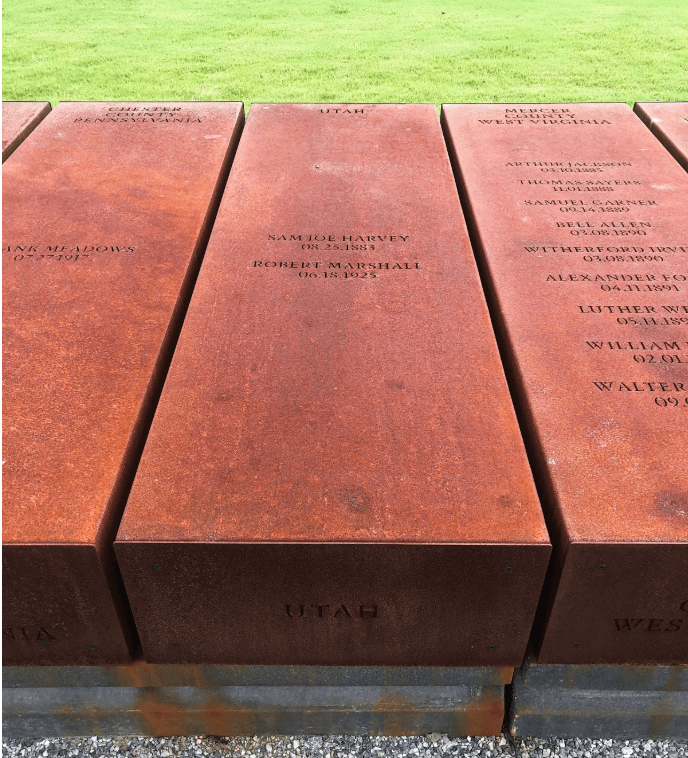

At the entrance, you are confronted with metal pillars bearing the names of those who died by lynching, arranged by county, gently corroding with rust. As you descend down the rectangular path, the pillars hold their ground. Anchored to the ceiling, you walk below the heavy blocks, rigid above you in the air. You can no longer read the names on the pillars; you stand under the weight of history, in the most corporeal sense.

Much of the initial backlash to the museum and memorial centered around the idea that these sites would too depressing: that we should be looking forward, not back, that dedicating space to past sins would just open up old wounds. There are a lot of reasons why this line of thinking doesn’t make sense, one being the pain of racial violence is still an active wound, and ignored wounds don’t tend to heal– they fester.

My personal experience was that there was nothing to be afraid of. Neither the museum nor the memorial was a place of despair. Like most memorials, this one felt somber, sacred. A space to make peace with those who had not received it. As my coworker Katie reflected after the fact, “as someone who identifies mostly as secular, I have to give credit to the people who designed the lynching memorial—it truly felt like holy ground.”

Something that surprised me was learning about lynchings that had taken place in Utah. The Equal Justice Initiative identifies two; other sites identify several more.

The memorial contains two pillars for every county included: one rooted in the memorial, and one available for that county to take home. Utah has the opportunity to claim our pillar– claim our role in its making– and create a memorial here. As we move forward in our mission to create a more just world, we can create space to remember and honor those who did not receive justice. It is my hope that our state and local leaders will take this opportunity seriously.